|

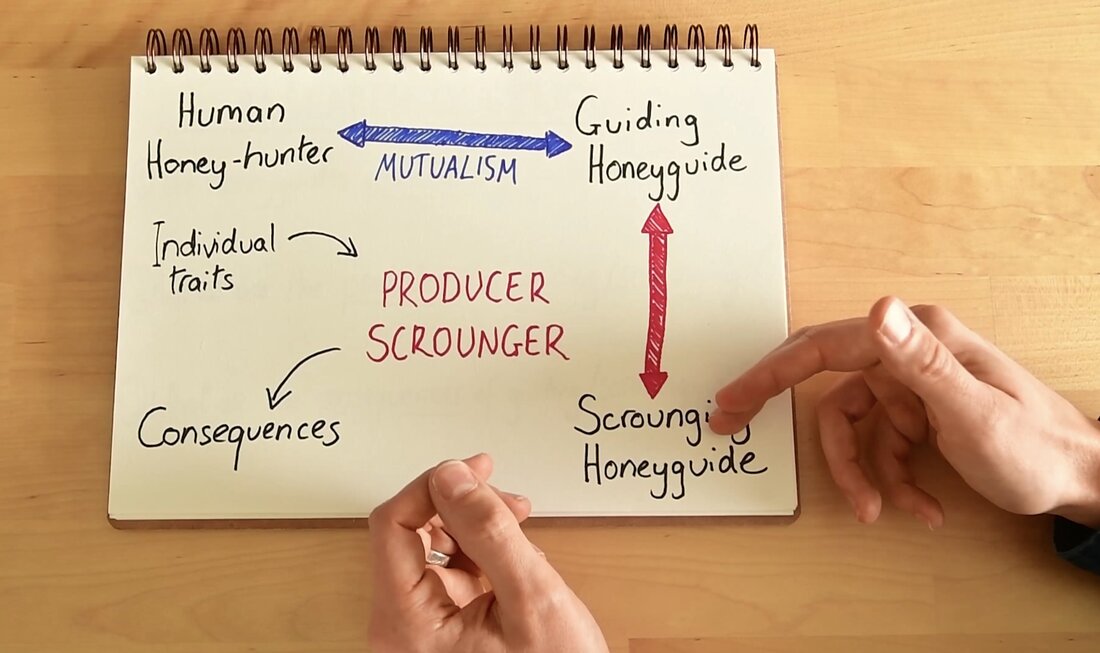

At a recent ASAB Virtual conference, I gave a 'notebook talk'. It was the most popular and talked-about presentation I've ever given. I thought I'd share some advice and tech tips for those wishing to create a similar talk. Click the image below to learn how to make and stream your own notebook presentation!

0 Comments

I'm delighted to reveal my new Wildlife Photography website. Wildlife photography has been my passion for over twenty years, and I'm thrilled to be able to share some of my favourite shots.

Visit domcramphotography.com to look through my portfolio, and please get in touch if you'd like to order a print. During WW2, several Pacific Islands suddenly gained great strategic value to both the Allies and Japan. These forces quickly attempted to establish island military bases. The communities that inhabited these islands suddenly experienced technology hundreds or even thousands of years more advanced than their own. Cargo planes and airdropped crates brought hundreds of tons of manufactured clothes, tinned food, tents, medicine, guns, tobacco, soap etc. These goods were intended to help the war effort, but they quickly found their way to the local communities, who often assisted troops by acting as hosts or guides. It must have been an inconceivable bonanza. Then, the war ended. The troops left and took almost everything with them. As quickly as the local people had lurched forward millennia, they lurched back again, but this time they knew what they were missing. In an attempt to summon more of the beloved goods, the communities re-created the conditions and peculiar rituals which led to the arrival of the bountiful cargo. They cut landing strips through the forest. They built planes and radar towers out of hay, and re-enacted military drills and marches. Generations later, improvised air-traffic controllers wearing coconut headphones still diligently signalled which runways were clear for landing.

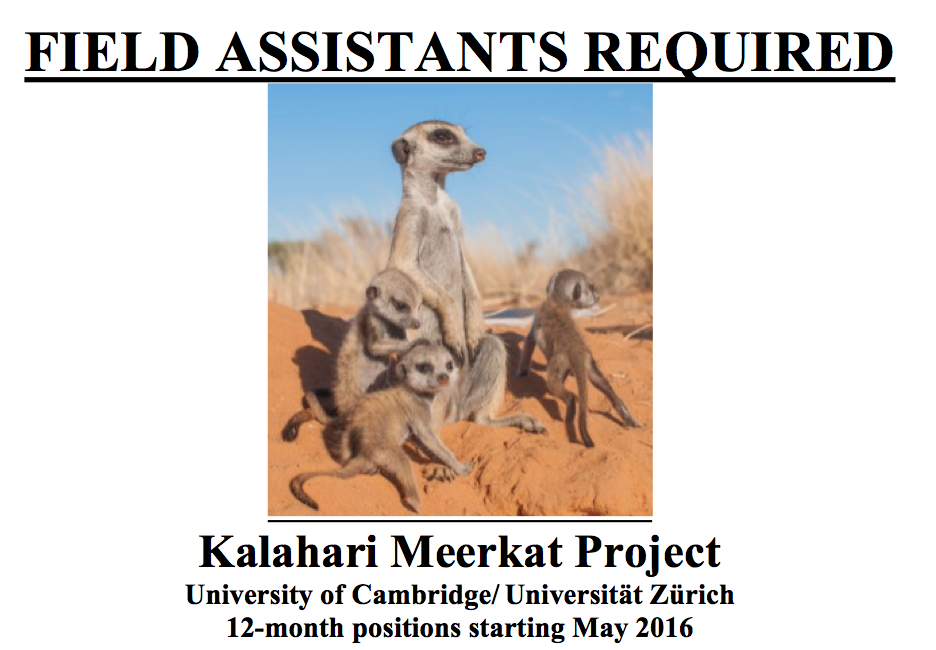

No planes came, and the well-meaning efforts were in vain. The older generation had accidentally bumbled into unimaginable progress and prosperity. Through no fault of their own, the younger generations never had any hopes of equality, and their attempts at replicating the good fortunes of their fathers and grandfathers were hopelessly misguided and doomed to failure. This is how it feels to be an unestablished academic today, and to hear the stories of those who secured lectureships in decades gone by.  I recently read David Eagleman's Sum, which is a collection of imagined after-lives. It is a work of "philoso-fiction", written in the hope that thinking about what happens after we die might help us think about all the things that happen before we die. You can find the full text for free here. This post is about the first chapter, which is less than 400 words long. In chapter one, your after-life is a replay of your first life, with one change. Your life's events are shuffled into a new order, with all the moments that share a quality grouped together. You drive and drive, only reaching your destination after 18 months. You spend a full thirty years asleep. Seven hours endlessly vomiting, two days tying your shoelaces. You shower for 200 days, do laundry for three months, and drink for 45 days, laugh for a week, fall over for 25 minutes. And then, for three minutes, you read a little book chapter about an alternative life. A life where activities are split into tiny enjoyable pieces. You do something until you're tired of it, and then do something else. You eat when you're hungry and stop when you're full. You can blissfully switch between events and do whatever takes your fancy, whatever excites you. You hop between activities so frequently you never tire of doing anything. For three minutes you ponder this infinite luxury. At its best, an academic research job in evolutionary biology is similar to this joyous patchwork. We think about ideas, read others' work, write code for analysis, plan experiments, peer-review submissions, produce presentations, buy equipment, collect data, write manuscripts, give seminars, meet colleagues, attend conferences, write press releases etc. Sometimes we do all of these, in as little as a week or two! Doing any of these things non-stop for more than a few weeks would quickly become unbearable. But switching between them is endlessly stimulating. I frequently feel jaded and depressed about the state of academic science, and my place in it. But it's worth remembering how good it is when it works. We're privileged to enjoy, as Eagleman puts it, "the joy of jumping from one activity to the next like a child hopping from spot to spot on the burning sand."  ... in meerkats, at least. Our new study has been published in Current Biology. (Click here for links to free PDFs of all my publications). This study was unusual because I embarked on it expecting a negative finding. For several years, some researchers studying highly social mammals had been strongly suggesting that dominant individuals in animal societies had special delayed ageing rates. We've known for a long time that dominant individuals tend to live longer than their subordinate counterparts, but do they have slowed ageing? If they do - billions should be spent studying them to unlock the secrets of staving off inevitable age-related declines in health. But do they? I suspected not. Slowed ageing rates that are somehow activated when an animal becomes dominant require some acrobatic physiology and evolutionary biology to explain. There is likely a simpler explanation. But with an open mind I set out to find out why dominants live longer, using the Kalahari Meerkats. For nearly two years we blood-sampled 35 meerkats repeatedly, to assess individual ageing rates. To do this, we analysed their blood telomeres, which are a genetic marker of cellular wear-and-tear that accumulates with ageing. The data revealed that, as expected, dominant meerkats outlived subordinates. However, we found that dominants' ageing rates were not slowed, but accelerated, compared to subordinates. Reproduction and status defence was taking its toll on the dominants' cells. So how do fast-ageing dominants outlive subordinates? We looked at other differences between these classes. For decades, scientists have followed the soap-opera dramas of meerkat day-to-day life. One frequent dramatic event is the disappearance of subordinates. Low-ranking females are violently kicked out of the group by the dominant female, and low-ranking males voluntarily trot off in search of mating opportunities, with both sexes usually returning after a few days. By contrast, dominants of both sexes never leave the group. We found that these trips away from the group were extremely dangerous, and solo subordinates were at risk of starving or feeding a nearby bird of prey. Dominants meanwhile enjoy the safety of the meerkat pack.

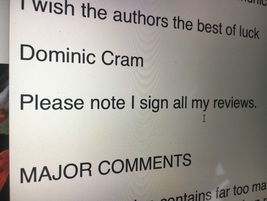

In short, dominants' lives aren't extended - subordinate lives are curtailed. Subordinates are not able to reproduce within their own group, so they are forced to leave the group and brave the dangerous Kalahari alone. Many do not survive. Those that do later become dominant themselves, and now have the good sense to never leave their group again. As a reward for reading this far, why not have a look at my Lego Summary of the paper in this Twitter thread? My paper investigating variation in meerkat pup telomere lengths has ben published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B. Hopefully the first of many meerkat telomere papers! Below is a summary of the paper’s findings, along with a personal reflection on the study.  We set out to investigate what factors affect telomere lengths in young meerkat pups. Telomeres are the protective caps on chromosomes, much like the plastic tips on your shoe-laces. Over time, those plastic tips get worn and frayed, and eventually they break off, which usually spells the end for those shoe-laces. The same is true for telomeres, which shorten and fray as individuals age, starting from birth. Short telomeres are bad news: other studies have shown they are associated with diseases and mortality. Our first set of results revealed that intense competition between pups was associated with shorter telomeres at roughly 1 month old. Meerkat pups with short telomeres at this early stage were less likely to survive into adulthood. Next, we looked for factors and strategies that might protect pups from short telomeres and reduced survival. First, we looked at food. Are pups competing over food? Is this why their telomeres shorten? If food competition is relaxed, are meerkat pups’ telomere protected? We tested this by experimentally feeding pregnant and lactating mothers. We found that pups from fed mothers had longer telomeres, regardless of the competition they faced. So pups are competing for food, and pups from well-fed mums are resilient and have longer telomeres! Next we looked at what mothers might do to protect their pups. Previous studies have shown that meerkat mums ruthlessly harrass other pregnant females, and mercilessly murder their pups. We wanted to investigate how these tactics affected the competition faced by their own pups, and whether this might impact their telomeres. We found that murderous meerkat mums typically kill 4 rival pups, reducing the competition faced by their own pups. We would predict this would be associated with a 7% increase in telomere lengths - quite a health boost!  This study was a huge endeavour, involving hundreds of meerkats, dozens of fieldworkers, hours of labwork and statistical analysis, and multiple drafts of the final paper. The paper contains six analyses - far more than I’d usually include. But each result posed new questions ["is this driven by food competition? what effect does infanticide have? are telomere lengths linked to survival?”] kept the process moving forward. The beauty of a large-scale, long-term natural dataset like the Kalahari Meerkat Project is that we could keep asking these questions. A similar paper written about almost any other species would have hit a brick wall labelled “not enough data”. A big 'thank you' to all those who helped with this study (that essentially means anybody who has collected data on our meerkats in the last 8 years!). On to the next project - investigating telomere lengths in adult meerkats!  Peer review is important. Like a guard by the gates to the garden of enlightenment, it ensures that only worthy pieces of scientific literature are widely disseminated. It blocks misleading, mistaken and down-right dangerous papers from gaining traction, affecting public opinion, shaping policy and wreaking havoc. Usually, anyway. But peer review is complicated. I've only been reviewing for a few years, and have only reviewed 12 papers, so I can't claim to be the world's foremost reviewer of biology manuscripts. What I can provide are the fresh (naive) thoughts of an early career researcher (ECR) and relative newcomer to the reviewing game. I've identified two main problems with writing and receiving peer reviews, and done my best to come up with solutions, after discussion with other ECRs (most notably Alecia Carter and Corina Logan). PROBLEM 1: Receiving peer reviews can be the most unpleasant piece of text you will read about yourself and your work, ever. Peer reviews rarely congratulate you for good ideas, hard work and gutsy attitude. Instead, they savagely highlight all the flaws. They can be rude, thoughtless and occasionally wrong, and are not a nice final step in the long journey towards a piece of scientific literature. SOLUTION: I sign all my reviews. Most reviewers don't want to be unpleasant, yet the cloak of anonymity means lapses into clumsy, cruel criticism do not have consequences. By signing all my reviews, I cannot accidentally write something unnecessarily harsh. I cannot forget to congratulate the authors for their hard work, and wish them luck with their paper (whatever the outcome). Instead, I write thoughtful, helpful, constructive reviews, even when I think the paper is garbage. This is usually very easy - most papers I review are good quality, and for the rest I don't feel that deciding to reject (albeit politely and helpfully) would bite me in the ass later in my career. Even in the worst-case-scenario (rejecting a paper from a rival lab) the decision to sign has not only been without cost, it has had huge benefits! I've been approached at conferences and workshops, and thanked for my helpful comments. I've been congratulated on the decision to sign reviews. The reviews I've signed have started chats about science that would otherwise never have happened. I STRONGLY encourage everyone to sign all their reviews, except where doing so would be life-threatening or completely career-ending. PROBLEM 2: Writing a helpful, constructive review (which you will have to do, if you are signing it!) is hard work for no money. SOLUTION: I only review for journals I consider 'ethical.' If I am donating my time and expertise, I need to ensure that the recipient is deserving! Journals that are for-profit, remove money from academia and are not open-access (or charge extortionate OA fees) clearly do not deserve charity from me. When I receive a request to review from an 'unethical' journal, I accept. I then immediately return a blank review, with a confidential note to the editor explaining my decision. For 'ethical' journals, I also include a confidential note, congratulating them on their policies and explaining my decision to review for them. As well as giving me the warm feeling that I'm contributing my time and brain to a worthy cause, this has the added benefit of screwing up and delaying the review process for 'unethical' journals. Don't feel too sorry for them: these journals charge authors publication fees, and then charge readers to access the papers. And most of the money is removed from academia. Why not use that money to pay for conferences, or grants, or studentships? Perhaps a clunky, delayed review process might encourage these journals to change their policies, or even encourage authors not to submit there anymore. So in summary: sign all your reviews, and don't do unpaid work for the bad guys. Simple. And as a reward for reading this far, here is a picture of a baby elephant shortly after crossing a river with its mother. Remember: the same task may be more challenging for some individuals than others. And it is not their fault. We are seeking two highly motivated field assistants to spend one year with our habituated meerkat population in the southern Kalahari Desert. For more info see our website

Hurry! The deadline for applications is 17th April 2016! The Southern Kalahari is currently suffering through its worst drought in over 20 years! There was less than 2mm rainfall per month in October, November and December 2015. We would normally expect 30mm per month during the so-called 'rainy season.'

This is having a devastating effect on the meerkats, which pregnancies failing, pups dying, and adults losing weight. Groups are forced to forage so widely that they end up separated, and can take several days to find one another.  Many hands make light work - my new open-access paper in Proceedings of the Royal Society B. In animal societies, cooperation can confer long-term benefits, including a boost to future breeding and survival. How can sharing a workload now allow an animal to breed more in the future? Equally, how can working hard now have a detrimental effect on future reproduction and longevity? I had a feeling oxidative stress may play a role. I wanted to test whether reproductive effort increased exposure to oxidative damage, and whether cooperative sharing of workloads could reduce these costs. To address this, I used a tricky clutch-removal experiment, lots of videos of feeding at the nest, and much blood sampling. The results revealed that, in small breeding groups, the costs of reproduction were clear: elevated exposure to harmful oxidative damage, which can lead to future diseases and ageing. However, in big breeding groups, there were no such costs. In larger social groups, additional helpers were sharing the burden of offspring care, and allowing all birds to avoid exposure to oxidative stress. Work rate even scaled with antioxidant protection: those that worked hardest had the weakest antioxidant defences. This was by far my favourite paper to emerge from my PhD research on the sparrow weaver project. The results suggest that oxidative stress may play a central role in the evolution of cooperation: while reproduction can carry significant costs, cooperative 'oxidative load-lightening' may have evolved to avoid these costs! |

Contact DOM:+44 seven seven nine two then 810760 Archives

June 2023

|